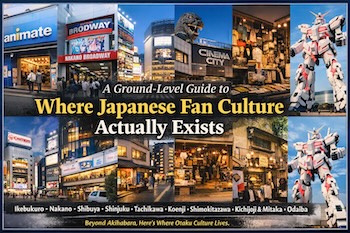

- A Ground-Level Guide to Where Japanese Fan Culture Actually Exists

- Ikebukuro: A District Built for Character-Based Fandom

- Nakano: Physical Media, Memory, and Resistance to Erasure

- Shinjuku: Scheduled Fandom Without a Center

- Shibuya: Disposable Culture With Maximum Impact

- Tachikawa: Cinema as a Pilgrimage Site

- Koenji: DIY, Zines, and Subcultural Crossovers

- Shimokitazawa: Fandom Meets Indie Identity

- Ueno: Figures, Art, and Hybrid Collecting

- Asakusabashi: Where Fans Build Their Own Goods

- Kichijoji and Mitaka: Gentle Fandom and Studio Ghibli Gravity

- Odaiba and Toyosu: Experience-Oriented Pop Culture

- [Extra Edition] World-class cute! TGC In Shizuoka

- Why There Is No “Next Akihabara”

A Ground-Level Guide to Where Japanese Fan Culture Actually Exists

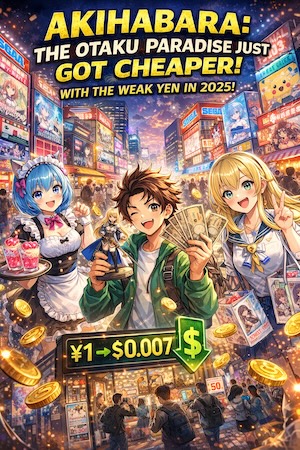

Akihabara is no longer the answer to a single question.

It is one node in a far larger system.

Tokyo’s otaku culture has spread horizontally across the city, reorganizing itself around function, gender, media format, and event cycles. What remains constant is not location, but behavior—where fans repeatedly gather, spend time, and return.

This article documents those places as they exist physically, through real shops, buildings, cinemas, and streets that fans actually use in now.

Ikebukuro: A District Built for Character-Based Fandom

Ikebukuro operates as a fully optimized fandom district, especially for character-driven and female-led communities.

The presence of Animate Ikebukuro flagship store alone defines the area. This is not a simple retail space; it is a vertical complex where release-day traffic control, exhibition spaces, and collaboration zones are planned as part of the building’s function. Entire weekends are shaped by what happens inside this structure.

Surrounding it, K-BOOKS maintains multiple specialized branches rather than a single megastore. One store may focus entirely on stage adaptations, another on character goods, another on idol or voice actor material. This separation reduces browsing friction and allows fans to move with intent rather than chance.

Rashinban Ikebukuro adds a resale layer that reflects recent event history. Goods tied to limited pop-ups, collaboration cafés, or theater productions reappear here weeks later, turning the area into a delayed archive of fandom movement.

Beyond retail, cafés such as Princess Café Ikebukuro function as scheduled gathering points. Menus, décor, and even customer flow change entirely depending on the collaboration, and visits are timed precisely to campaign periods.

Ikebukuro does not preserve culture.

It synchronizes with release cycles.

↓I’m also considering Ikebukuro-related considerations. Please take a look!↓

Akihabara vs Ikebukuro |Two Otaku Capitals, Two Completely Different Rulebooks

Recommended Women’s Complete Guide | Ikebukuro and Akihabara Street Walking Saved Version

Why Ikebukuro Became Japans Oshi Katsu Capital

Nakano: Physical Media, Memory, and Resistance to Erasure

Nakano’s role is not to follow trends, but to outlast them.

Inside Nakano Broadway, stores like Mandarake Complex operate at a scale unmatched elsewhere in Tokyo. Floors are divided by genre and era, not popularity. Animation cels, vintage figures, discontinued toys, old idol merchandise, and obscure doujin works exist side by side without hierarchy.

Smaller spaces such as Graveyard Gallery Nakano reinforce this archival identity by hosting exhibitions focused on tokusatsu, horror, and retro pop culture. These events attract collectors rather than tourists, and attendance often consists of repeat visitors who track exhibitions closely.

Nakano rewards patience and knowledge.

It is not designed to be friendly.

That is precisely why it remains relevant.

Shinjuku: Scheduled Fandom Without a Center

Shinjuku does not announce itself as an otaku district, yet it hosts some of the most important fandom moments in Tokyo.

Cinemas such as Shinjuku Wald 9 and Shinjuku Piccadilly regularly host advance screenings, stage greetings, and themed events for major anime films. Fans travel here for specific dates, not for browsing.

Retail spaces like Animate Shinjuku exist within the city’s commercial grid rather than outside it. This allows fans to combine fandom activity with dining, shopping, and nightlife without changing districts.

Redeveloped zones around Kabukicho increasingly host esports events and pop-culture collaborations, often without explicit otaku branding. The audience, however, overlaps heavily.

Shinjuku does not gather fans permanently.

It activates them temporarily.

Shibuya: Disposable Culture With Maximum Impact

Shibuya thrives on impermanence.

Inside Shibuya PARCO, entire floors transform into anime, game, and VTuber collaboration spaces for weeks at a time. Apparel, goods, and themed cafés appear, dominate social media, and vanish.

Fashion brands participate directly, producing limited-run items tied to specific franchises. Sales are driven by visibility and timing, not long-term collection.

Shibuya favors fans who move fast.

Miss the window, and the culture is gone.

Tachikawa: Cinema as a Pilgrimage Site

Tachikawa’s reputation rests heavily on Tachikawa Cinema City.

Known for its advanced sound systems, this cinema attracts anime fans willing to travel for audio quality alone. Some films run here far longer than in central Tokyo due to repeat attendance.

The surrounding area supports this behavior. Cafés, walkable streets, and relatively low congestion create an environment where fans stay, talk, and return.

Tachikawa does not sell fandom aggressively.

It respects serious viewers.

Koenji: DIY, Zines, and Subcultural Crossovers

Koenji represents a different branch of otaku culture—creation over consumption.

Here, anime fandom overlaps with indie music, vintage fashion, and self-published works. Small shops and event spaces host zines, handmade goods, and experimental expressions that rarely appear in mainstream districts.

Koenji’s value lies in local continuity rather than visibility. Fans return because they belong, not because something is new.

Shimokitazawa: Fandom Meets Indie Identity

Shimokitazawa blends anime culture with alternative fashion and music scenes.

Stores like Village Vanguard Shimokitazawa stock character goods alongside lifestyle items, while cafés and pop-up spaces host short-term collaborations aimed at younger, SNS-driven fans.

Anime connections here are often indirect—through live performances, themed cafés, or works that use the area as a setting. The culture feels casual, not institutional.

Ueno: Figures, Art, and Hybrid Collecting

Ueno’s otaku presence hides behind its museums and markets.

Shops such as Yamashiroya operate multi-floor layouts focused on figures and character goods, attracting collectors who prefer physical inspection over online orders. Nearby specialty stores cater to film, Western characters, and imported items.

Exhibition spaces like The Ueno Royal Museum and Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum frequently host animation-related exhibitions, creating a bridge between fine art audiences and fandom.

Asakusabashi: Where Fans Build Their Own Goods

Asakusabashi is not a consumption district.

It is a production zone.

Stores like Kiwa Seisakusho Asakusabashi flagship and Parts Club supply materials for ita-bags, custom accessories, and display items. Fans come here to assemble, not to buy finished products.

The proximity to Akihabara adds to its utility, but the culture here is quieter and purpose-driven.

Kichijoji and Mitaka: Gentle Fandom and Studio Ghibli Gravity

Kichijoji and Mitaka offer a slower form of otaku culture.

The presence of Ghibli Museum, Mitaka draws fans worldwide, but the surrounding area supports casual exploration—bookshops, cafés, and small pop-ups rather than dense retail.

This area appeals to fans who prefer atmosphere over accumulation.

Odaiba and Toyosu: Experience-Oriented Pop Culture

In Odaiba, landmarks such as The Gundam Base Tokyo turn fandom into spectacle. Large-scale displays, limited goods, and photo opportunities define the experience.

Toyosu hosts large live venues like Toyosu PIT, frequently used for anime and game-related events. Fans come for scale and immersion rather than daily shopping.

[Extra Edition] World-class cute! TGC In Shizuoka

Although it is not in Tokyo, it is an international event, and let me introduce this Shizuoka, where a “cute” first-generation event that attracts attention from around the world will be held.You can travel quickly from Tokyo by Shinkansen!It’s the prefecture where the famous /^o^\ Mt. Fuji is located.Many music festivals are also held in this blood.

Why There Is No “Next Akihabara”

Tokyo no longer needs a single center.

Fandom now organizes itself around events, media formats, and personal identity, not geography alone. Each district listed here serves a specific function, and fans move between them fluidly.

Searching for one sacred place misses the point.

The culture survives because it spreads.

Quotation and reference

I quoted and referred to the information from this article.

We deeply consider and experience Japanese otaku culture!

[Tokyo’s Otaku Town] It’s not just Akihabara! Anime & Subculture Holy Land Summary Latest Version / Ikebukuro, Shinjuku, Nakano, Tachikawa, Shibuya, etc…|akihabara.site Official

All Write: Kumao